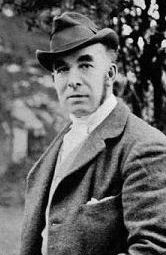

Ever

since listening to “The Real Trial Of Oscar Wilde” on Radio Four

a couple of week ago, I've been pondering the tragic downfall of this

theatrical genius.

At

the height of his career, Oscar Wilde was found guilty of gross

indecency and imprisoned for two years. He was subjected to a harsh

regime of ' hard labour, hard fare and hard bed' which left

him mentally and physically exhausted. He was forced to flee to Paris

after his release and he died at the age of 46 with his reputation in

shatters, his health destroyed and his fortune depleted.

|

| Oscar Wilde |

Wilde,

of course, was a homosexual and homosexuality wasn't decriminalised

in the UK until 1967. But the late Victorian period wasn't nearly as

prudish as popular culture would make us believe. There was a very

active gay scene in London at the time and Wilde's sexual orientation

was something of an open secret amongst the theatrical community.

Wilde made very little attempt at disguising his relationship with

the young Lord Alfred Douglas (aka Bosie) and everyone knew that the

two were more than just good friends. Wilde's

incarceration was not the result of a puritan society frowning on his

immoral activities (the Victorians were generally not concerned with

what went on between consenting adults, so long as it happened in private) Wilde was

incarcerated because, much like Vicky Pryce in recent years, he used

the law to get satisfaction in his own private vendetta. And lost.

There

were two trials which led to his downfall. The first one was

instigated by Wilde himself after the Marquess of Queensberry

(Bosie's father) left his calling card at his club accusing him of

being a sodomite. Wilde became indignant and accused Queensberry of

libel.

This

was an extraordinarily foolhardy thing to do considering both he and

Bosie had been very open and reckless in their dealings with rent

boys and homosexual brothels. The onus was now on Queensberry to

prove that Wilde was a depraved older man who habitually enticed

naive youths into a life of vicious homosexuality.

|

| The Marquess Of Queensberry |

Wilde

was smugly confident at first that he could outwit Queensberry's

lawyers with his eloquence. He viewed the whole trial as a game of

words which he was sure to win – after all, although Wilde readily

admitted to consorting with young men of low class, it was almost

impossible in an age before the ubiquitous presence of cameras to

prove that any homosexual activity had actually taken place. Wilde

relied heavily in endearing himself to the court by resorting to

humour and witty retorts and exposing Queensberry for the pompous and

blundering old fool that he was. But it was exactly this flippancy

which led to his downfall. When Wilde was asked whether he had ever

kissed a certain servant boy, Wilde responded, "Oh,

dear no. He was a particularly plain boy – unfortunately ugly – I

pitied him for it."

When he was then asked why

the boy's ugliness was relevant, Wilde hesitated and for the first

time became flustered: "You

sting me and insult me and try to unnerve me,”

he said, “and

at times one says things flippantly when one ought to speak more

seriously.”

It

didn't take long after that for Queensberry to assemble enough

evidence to prove his accusation. His lawyers paid rent boys to secure their damming testimonies and Wilde was soon

forced to drop the case. He was now faced with debilitating legal

charges and, having so publicly incriminated himself, the authorities

had no option but to arrest him for gross indecency. This led to the

second trial and eventually to his own destruction.

So

why did this play affect me so? Well, it was Wilde's foolhardy

decision to prosecute Queensberry which intrigues me. What was he

thinking? What was behind this self destructive streak? Well, the fact is that Wilde was being used by Bosie to get back at his father. Bosie had a very troubled relationship with

Queensberry, whom he despised. Whereas Bosie was sensitive and

artistic, Queensberry was a bully and a brute and was more interested

in the art of fighting than in his son's poetry (This is the same

Queensberry who composed the famous boxing rules). Queensberry

looked down on his son. He considered him a sissy and a weakling and

never ceased tormenting him. He was fiercely opposed to Bosie's

relationship with Wilde and was dead set on separating the two. In

fact he had a bee in his bonnet about older men trying to corrupt his

sons. He had already accused Rosebery, the liberal statesman and

future prime minister, of having a homosexual affair with his elder

son Francis who worked for him as his private secretary. Francis died

in a suspicious hunting accident, which some believe may have been a

suicide resulting from his father's threats to expose him. Bosie was

deeply affected by his brother's death and as far as Wilde was

concerned, this was the last straw. Encouraged by Bosie, Wilde took

Queensberry to court in an attempt to put to an end his incessant

bullying, but as we have seen, it all backfired in the most tragic

fashion.

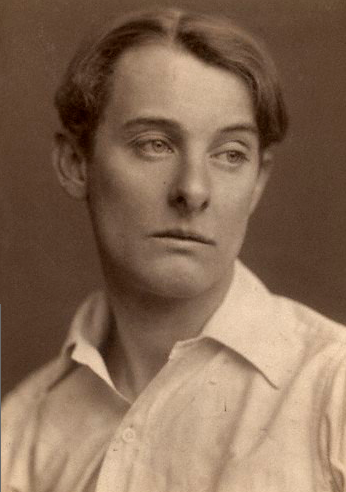

|

| Lord Alfred Douglas (aka Bosie) |

The

trials of Oscar Wilde were a great sensation at the time and many

films, books and plays have been written about it, all of which try to illuminate what was really going on in Wilde's mind when he embarked on this spectacular feat of self

destruction. Was he a fool for love? A martyr for the gay cause? A

shameless attention seeker?

A certain phrase I once stumbled upon while reading Robinson Crusoe came to mind as I listened to the play. It is a phrase which intrigues me and which has subsequently become the underlying sentiment in my forthcoming novel “The Ornamental Hermit”:

A certain phrase I once stumbled upon while reading Robinson Crusoe came to mind as I listened to the play. It is a phrase which intrigues me and which has subsequently become the underlying sentiment in my forthcoming novel “The Ornamental Hermit”:

‘It is a secret overruling decree that hurries us on to be the instruments of our own destruction. Even though it be before us we rush upon it with our eyes wide open’.

No comments:

Post a Comment